EUROPE'S CO-OPERATIVE AND SOLIDARITY ROOTS

Europe is a vastly diverse continent with different cultures, languages, and economies. If there is something that unites it, it is its social and civic movements, the roots of which reach far into the origins of the workers co-operative movement of the 19th century, the mutualistic practices, the public and private community banks and credit unions, the consumer groups and networks, the workers’ unions and the many cultural and care-oriented associations at the core of the welfare state development. The 20th century, through numerous struggles and cultural shifts, has brought European citizens a relative well-being and affirmations of rights, both individual and collective, though often excluding minorities, impoverished or discriminated parts of the population. Far from being fulfilled (in different ways in each country or territory), the concrete vision of a socially just, democratic and inclusive society where the realisation of universal human rights is ensured for all the people, is continuously challenged today. The 21st century has begun with a new wave of reactionary ideologies. This has led to the

introduction of austerity measures, more deregulation and privatisation and other neoliberal policies, all of which are undermining its core: economic democracy and self-determination. The recent “globalised” pandemic COVID19 crisis has added to the existing crises, highlighting the root causes of disparities in our societies. It also emphasizes the fragility of an outdated economic system that is based on the concepts of growth, profit, competition and extractivism, as well as the inability of public institutions and policies to provide communities with concrete, collective solutions.

At the same time, the growing legislative recognition of Social Solidarity Economy by many European countries is an increasing reality. Existing and prospective legislation in EU member countries reveals many differences and few similarities. This reflects the need of an over-arching European legislative framework, which is not simple, given the contradictions in the existing EU policies. Some countries have an existing or projected national legislative framework (France, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Romania), others have a Minister for

Social and Solidarity Economy (Luxembourg, Spain and France). Some other countries have a series of regional norms (this is the case in Italy, where 10 regions have made different laws for the promotion of solidarity and sustainable economy).

SOCIAL SOLIDARITY ECONOMY: A VECTOR FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

...“solidarity” is much more than a concept. First, it is a frame-work for designing and implementing strategies that strengthen the resilience of communities, regions, and societies. Second, it elevates the idea of advancing the common good collaboratively rather than going it alone. Third, solidarity is a vital motivational resource, and a renewable one. It is a resource that we need from each other in order to sustain the efforts transition will require.

SSE should be considered as a movement composed of a plurality of actors, (private, social, public – formal and informal), building active bonds between civil society, policy-makers, production and services’ sectors to address peoples’ needs, aspirations and expectations. Karl Polanyi expressed this well in the “The Great Transformation, the political and economic origins of our times”: we need to retrieve a broader definition of the economy, we cannot equate it with the Market. A new form of economy cannot arise from within the dominant financial and economic system unless it deeply changes how people imagine ways to address their needs and desires and feel part of a broader community. That is why SSE is not to be merely identified as the Third Sector (Non Profit or Social Sector), but as a vector of practices and values that allow us to see our world differently.

It is also important to clarify some terms: it is very common for the social economy to be conflated with the solidarity economy. They are not the same thing and the implications of equating them are rather profound. The social economy is commonly understood as part of a “third sector” of the economy, complementing the “first sector” (private/profit-oriented) and the “second sector” (public/planned). While exact definitions of the social economy vary, a common definition is that it includes co-operatives, mutual societies, associations, and foundation (CMAFs), all of which are collectively organized, and oriented around social aims that are prioritized above profits, or return to shareholders. The primary concern of the social economy is not to maximize profits, but to achieve social goals (which does not exclude making a profit, necessary for reinvestment, for instance). Some people consider the social economy to be the third leg of capitalism, along with the public and the private sector. Others view the social economy as a stepping stone towards a more fundamental transformation of the economic system and organisation of our communities.

The solidarity economy (c.f. diagramme below) seeks to change the whole social/economic system and puts forth a different para-digm of development that upholds human rights, social justice, solidarity and ecological practices. It pursues the transformation of the economic system from a market-based capitalist model that gives primacy to maximising private profit and blind growth to that of a radically different and sustainable economic model that places people and the planet at its core. As an alternative economic system, the solidarity economy thus includes all three sectors private, public and the social sector.

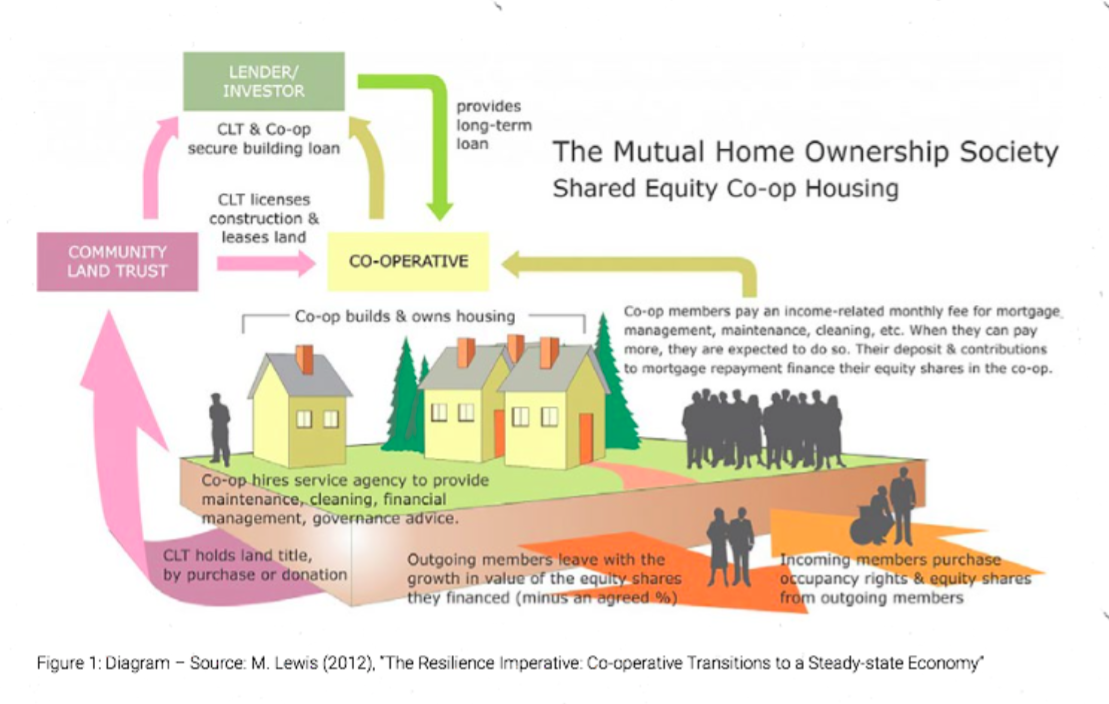

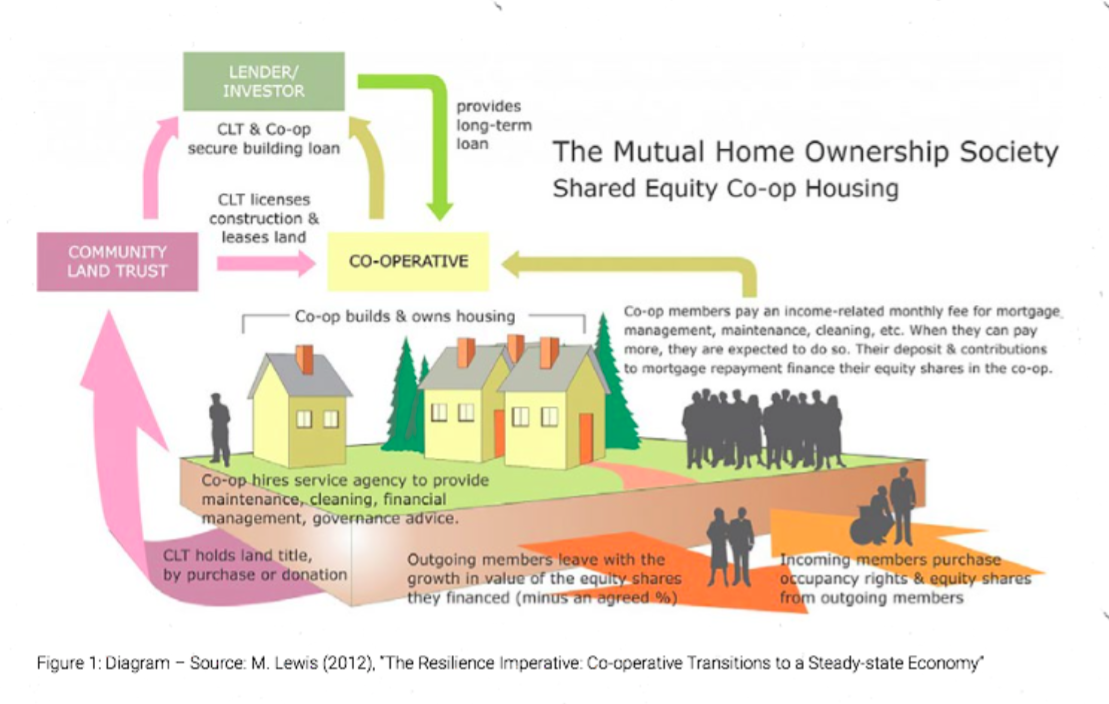

Since it is not a sector of the economy, but a vector of change and transformation of the economic system, it cannot be easily measured through official indicators or statistics and is there-fore remain for the most part “invisible”. According to the last Figure 1: Diagram – Source: M. Lewis (2012), “The Resilience Imperative: Co-operative Transitions to a Steady-state Economy”

available EU statistics, workers in Third Sector increased in the first 15 years of this century from 11 million to 16 million, or an average of 6.5 % of the working population of the EU (with some countries reaching almost 15%). This number does not include all the informal approaches and the mixed forms of SSE practices and initiatives (from alternative production and co-construction to barter, social currencies, time banks, etc.) or the role of many local public administrations that support and promote them. Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) groups, Solidarity Consumer and Producer Groups are a practice that is multiplying in many forms: from a few hundred at the end of the 1990s and only in two-three countries, to tens of thousands in 2020. In 2015, there were over 1 million people in Europe involved in CSA.